Dornbirn-GFC 2020 cancelled

Opinion

Superficial changes block the path to real innovation, conference hears.

27th September 2024

Adrian Wilson

|

Dornbirn, Austria

A ‘Pandora’s Box’ was opened 30 years ago in the form of the amendments to GATT – the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade – which paved the way for the formation of the World Trade Association in 1995 and today’s fragile system, according to Arthur Erdem of Vienna-based IPEF Consulting.

He was speaking at the recent three-day Dornbirn Global Fiber Conference (GFC, September 11-13) in Austria, as part of an illuminating cross-sector session featuring experts from the paper and packaging sectors. Both of these sectors employ fibrous materials and as a result of legislation are further down the route to sustainable production than the textiles industry in many areas.

“Free trade agreements such as GATT allowed multinational companies to relocate production facilities to low wage countries,” Erdem said. “This led to job losses and wage pressure in industrialised nations, while at the same time working conditions remained precarious in many developing countries. Globalisation and intense competition between companies reduced the pressure on governments to protect strong labour rights and these rights were often sacrificed in favour of lower production costs.”

Corporate power

He added that this increased global trade promoted export-oriented agriculture and industrial production, which led to increased resource consumption and environmental degradation. Consideration for environmental standards was often neglected as the focus was on competitiveness.

In turn, the enforcement of international trade regulations resulted in states surrendering some of their economic sovereignty to international organisations such as the WTO.

“States had less leeway to enforce protectionist measures to protect local industries or environmental regulations, which led to the increased power of corporations,” Erdem said. “Large multinational companies benefited greatly from the liberalisation of trade, while smaller, locally oriented companies were often at a disadvantage. This led to an increasing concentration of economic power in the hands of a few global corporations.”

The expansion of free trade created complex, global supply chains that made countries more vulnerable to external shocks, he added.

“This was particularly evident in crises, such as the Covid 19 pandemic, when supply chains were severely disrupted.”

Consumption growth

Some sobering statistics were presented to back up these observations.

In Austria, for example, per capita household waste in 1995 was 424 kg and by 2021 had grown to 860 kg – a rise of 102%, despite population growth of only 12.6%,

In Germany, packaging waste generated in 1995 was 15.6 million tons and by 2021 had grown to 19.7 million tons – a 26% increase, despite only 2% population growth.

Back in 1995, there was an average of 8,000 separate items on German supermarket shelves and now there are over 15,000 – a rise of approximately 86%.

“Back in 1995 there was a choice of 20 yoghurts, for example, and now we are up to 150, with 80% of them processed,” Erdem observed. “E-commerce in Germany has grown in just a few short years by 4,082%, from 27.5 billion items in 2020 to 1.15 trillion in 2023, with 100-150 billion items just food, so we are now packing food, packing it again and sending it around the world. What were we doing without in 1995 that we have now? The answer is nothing, yet we now support a system with so many articles on the market.”

Mass balance

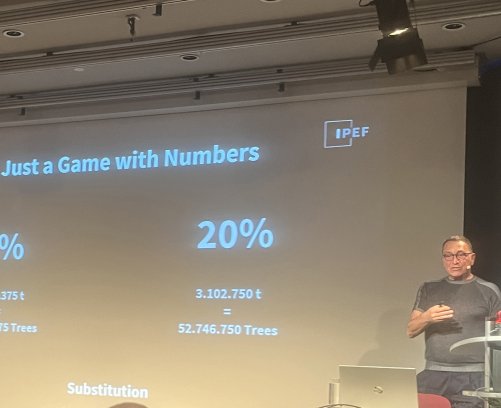

Even when lower volume products are supplied, mass balance remains the same, Erdem explained, because often the packaging material consumption stays the same regardless of whether sustainable or recycled substrates are employed or not.

“Substitution is not sustainability,” he said. “To substitute 10% of plastic packaging with paper in Germany would require 1.5 million tons of paper – 26 million trees. Substitution is in fact a measure to prolong the life of a system that is doomed. Instead of mustering the courage to make the right systemic choices and to recognise the uncomfortable truths of our time, we cling to the hope that our survival can be ensured by substitution, be it of materials, energy sources or processes. This is a dangerous fallacy.

“Science is unforgiving and a mass balance is a mass balance. A system designed to consume resources and produce waste remains destructive even if you replace some of its parts with more sustainable alternatives.

“This kind of thinking hinders the true transformation needed to ensure a sustainable future. By focusing on superficial changes, we block the path to real innovation, which would require a profound transformation of our economic and living conditions.

“Most of us know little to nothing about the complex interactions that shape our natural and economic systems, yet we have learned one thing – to hide behind sustainability reports and regulatory requirements while collectively pretending that all of this is the solution to our problems.”

Business intelligence for the fibre, textiles and apparel industries: technologies, innovations, markets, investments, trade policy, sourcing, strategy...

Find out more