Consumer desire for portable exoskeleton

Thermoplastic elastomer is several times more flexible than the thermoplastics used previously.

18th March 2025

Innovation in Textiles

|

Cambridge, MA, USA

MIT researchers have embedded a series of microdevices into a single elastic fibre to create an autonomous programmable computer which can monitor health conditions and physical activity.

Sensors, a microcontroller, digital memory, bluetooth modules, optical communications and a battery are all embedded in the fibre, which is nearly imperceptible when integrated into clothing.

Unlike on-body wearables which are located at a single point such as the chest, wrist or finger, fabrics and apparel have the advantage of being in contact with large areas of the body close to vital organs. As such, they present a unique opportunity to measure and understand human physiology and health.

The researchers added four fibre computers to a top and a pair of leggings, with the fibres running along each limb. In their experiments, each independently programmable fibre computer operated a machine-learning model that was trained to autonomously recognise exercises performed by the wearer, resulting in an average accuracy of about 70%.

Surprisingly, once the researchers allowed the individual fibre computers to communicate among themselves, their collective accuracy increased to nearly 95%.

Gigabytes of data

“Our bodies broadcast gigabytes of data through the skin every second in the form of heat, sound, biochemicals, electrical potentials and light – all of which carry information about our activities, emotions and health,” says Yoel Fink,professor of materials science and engineering at MIT and principal investigator at the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE) and the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies (ISN). “Unfortunately, most, if not all of it gets absorbed and then lost in the clothes we wear. We’re aiming to teach clothes to capture, analyze, store and communicate this important information.”

The fibre computer builds on more than a decade of work at the RLE and was supported primarily by ISN. In previous papers, the researchers demonstrated methods for incorporating semiconductor devices, optical diodes, memory units, elastic electrical contacts and sensors into fibres that could be formed into fabrics and garments.

“We hit a wall in terms of the complexity of the devices we could incorporate because of how we were making it and had to rethink the whole process,” Nikhil Gupta, an MIT materials science and engineering graduate student working on the project. “At the same time, we wanted to make it elastic and flexible so it would match the properties of traditional fabrics.”

Geometric mismatch

One of the challenges the researchers surmounted is the geometric mismatch between a cylindrical fibre and a planar chip. Connecting wires to small, conductive areas, known as pads, on the outside of each planar microdevice proved to be difficult and prone to failure because complex microdevices have many pads, making it increasingly difficult to find room to attach each wire reliably.

For the latest design, the researchers map the 2D pad alignment of each microdevice to a 3D layout using a flexible circuit board called an interposer which they wrapped into a cylinder. They call this the “maki” design. They then attach four separate wires to the sides of the maki roll and connect all the components together.

“This advance was crucial for us in terms of being able to incorporate higher functionality computing elements, like the microcontroller and Bluetooth sensor,” says Gupta.

The versatile folding technique could be used with a variety of microelectronic devices.

In addition, the researchers fabricated the new fibre computer using a type of thermoplastic elastomer that is several times more flexible than the thermoplastics used previously. This material enabled the formation of a machine-washable, elastic fibre that can stretch more than 60% without failure.

The fibre computer is produced using a thermal draw process pioneered in the early 2000s which involves creating a macroscopic version of the fibre computer, or preform, that contains each connected microdevice.

The preform is hung in a furnace, melted and drawn to form a fibre, which also contains embedded lithium-ion batteries so it can power itself.

Arctic insights

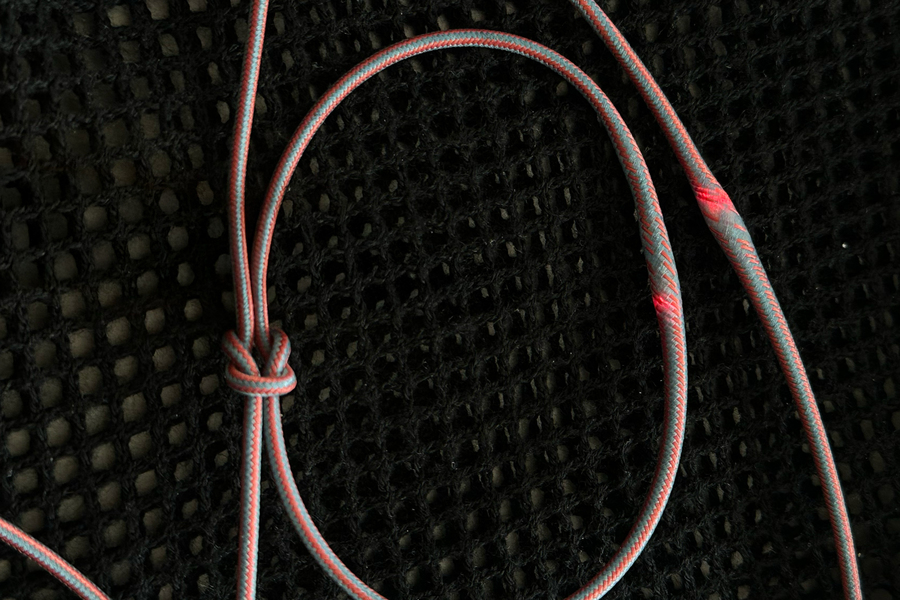

The use of the fibre computer to understand health conditions and help prevent injury has recently undergone a significant real-world test. In February, US Army and Navy service members conducted a month-long winter research mission to the Arctic, covering 1,000 kilometres in average temperatures of –40 degrees Fahrenheit. Dozens of base layer merino mesh shirts with fibre computers have provided real-time information on the health and activity of the individuals participating on this mission, called Musk Ox II.

“In the not-too-distant future, fibre computers will allow us to run apps and get valuable health care and safety services from simple everyday apparel,” Fink concludes.

Business intelligence for the fibre, textiles and apparel industries: technologies, innovations, markets, investments, trade policy, sourcing, strategy...

Find out more