Zara collection based on 100% Circ Lyocell

Innovation In Textiles talks to Peter Majeranowski, CEO and president of Danville, Virginia-headquartered new fibre tech pioneer Circ.

31st July 2024

Innovation in Textiles

|

Danville, VA, USA

Innovation in Textiles (IiT): What’s the background to Circ and how did the company come into being?

Peter Majeranowski (PM): Circ’s origins are in plant sciences, and we were initially processing biomass to make biofuels. Back at the death of the era we call Cleantech 1.0 there was a lot of investment in biofuels that wasn’t working out and the investment community pretty much shut the door on continued investment, so we had to find another application for our tech.

We looked first at recycling packaging and then by chance at recycling textiles. We started with cotton and then polyester, before we specifically moved to polycotton blends. That was back in 2017. We got promising results almost immediately and we knew our technology worked at the lab scale. At the time we didn’t recognise how big a problem textile waste was. It was the Ellen MacArthur Foundation white paper on the circular economy for textiles that really opened our eyes and made us realise that this was a problem the industry had started to get its arms around and needed to be addressed and fixed. We joined Fashion for Good in its early development stage and were adopted into its scaling programme and the word got out.

This was the first time for us as a company that we had brands cold calling us and asking how much material we had, so we subsequently opted to focus the company completely on textile recycling.

IIT: How successfully have you been able to attract the necessary funding?

PM: We raised our first institutional money in 2019 led by the corporate venture arm of Patagonia and were able to bring in Marubeni, the big Japanese trading house, which allowed us to scale out of the laboratory to pilot scale. We were then able to raise more money in a round led by Breakthrough Energy Ventures, founded by Bill Gates, joined by Inditex, Temasek from Singapore and Landsdowne of London.

We now have a good mix of financial investors and brands and retailers – Zalando is another example – as well as backers from the supply chain, like Milliken, Avery Dennison, Youngone and most recently, Taiwan’s Far Eastern.

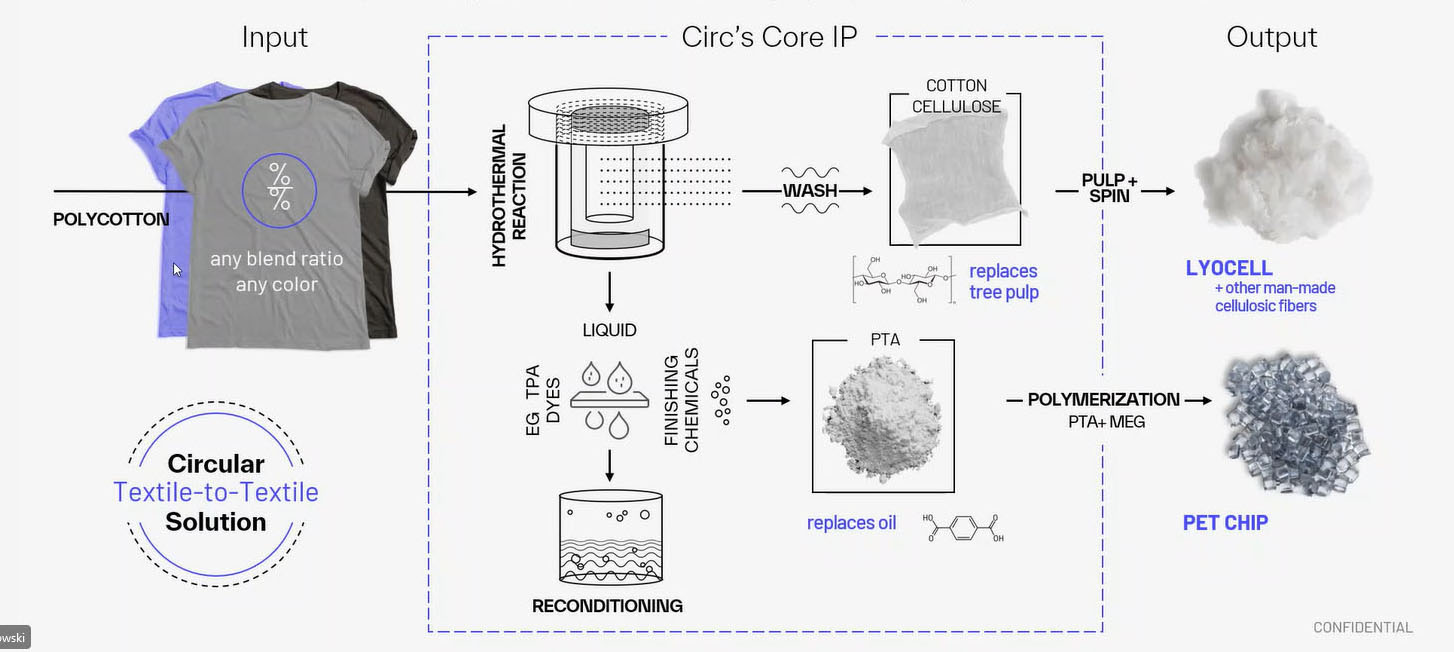

IIT: Your technology is pretty unique in separating both polyester and cotton/cellulose in blended fabrics. How does it work?

PM: What’s really tough about textile recycling at the moment, is that the majority of textiles are in polycotton blends. There are a lot of reasons for these blends, but of course the main one is cost – a t-shirt has cost ten pounds for the last forty years and this has happened by blending in more poly with cotton, as well as moving production to cheaper and cheaper places.

Our process can take polycotton material in any blend ratio and any colour. We’ve worked with post-consumer waste, which is how Patagonia first got interested when establishing its take back programme, and we’ve also worked with pre-consumer waste. There’s so much unsold inventory and there are also returns, damaged inventory and then post-industrial waste. To make a shirt, you need almost another shirt’s worth of material that’s wasted in the supply chain from making yarns, then fabrics then cut and sew.

Our IP begins with a hydrothermal reaction which is the science we developed for biofuels that we’ve now modified for what we’re doing with textiles.

A number of things happen in this first step and the key one is that we break down the polyester through depolymerization by hydrolysis. As this takes place, the separation also occurs. When we break down the polyester into monomers it dissolves into the liquid and results in two streams – the solid stream with just the cotton that’s left over and the liquid stream, which not only contains the polymer but also the dyes, finishing chemistries and coatings.

We tune the cotton cellulose so that it can be used in existing processes for manmade cellulosic fibres such as lyocell, viscose, modal, cupro etc., and from the liquid, we carry out an extraction and purification of the monomers.

IIT: And this includes the PTA (purified terephthalic acid) monomer?

PM: It does – we’ve developed a purification method here working with Professor Alan Myers of MIT and this is IP we’re very proud of because 99.9% purity here won’t necessarily work – you have to make sure you screen out certain impurities that would prevent the PTA – which makes up roughly 70% by weight of polyester – from repolymerising.

This first step works through subcritical water technology, but essentially we take the raw material, shred it, put it into this first processing step, add water and temperature, but don’t allow it to flash to steam – that’s the subcritical water part. We keep it under pressure and when you add a little bit of responsible chemistry the breaking down of the polyester and separation happens very quickly.

We’ve been piloting for over three years just to get consistent results, testing a wide variety of feedstocks and doing a lot of engineering. You need to show the hours of operation to get to the next scale.

Our monomers then go to partners like Far Eastern to be turned into polyester and chips and our cellulose is going to lyocell and viscose producers. We’ve primarily worked in lyocell because it’s more of a preferred fibre, but we’ve also made viscose with our material.

IIT: What kind of yield can you typically get from the process?

PM: Overall, we have a recovery rate of about 90%. The challenge whenever you work with natural fibres is they get shorter all the time on a molecular level, to the point where they turn into sugars, so there are always losses similar to in paper recycling.

On the polyester side though, we have a very high recovery and it’s more about process loss from step to step, but theoretically you can infinitely recycle polyester through depolymerising and repolymerising it.

IIT: What problems do elastanes pose?

PM: Elastanes are tricky, and our system can’t recycle them. We don’t break them down. We’ve taken waste with small amounts but we prefer not to. Since our focus is on polycotton, the elastane simply becomes a waste product.

IIT: So, what are the obstacles to commercialisation and what stage are you currently at?

PM: We are currently at technology readiness level (TRL) 7 and now aim to get fully to industrial scale.

One challenge is that the textiles industry is very old and optimised but also very fragmented, with not a single major brand responsible for taking more than 1% of what’s produced.

There’s a lot of money waiting for financing large scale facilities but investors want to see long-term purchase commitments from the brands, who don’t typically buy more than one season ahead. And they definitely don’t buy PTA or cellulose. So the situation is a little bit complicated.

In the past 12 months, however, we’ve seen that the appetite has gone up because the regulations and policies are starting to come into force.

It’s becoming apparent that brands who don’t secure offtake agreements now are going to miss the race, because even if all of the new fibre companies that are emerging build five factories each, this will still only meet single digit demand and the circular fibres they’ll need simply won’t be available.

For our part, we aim to be commissioning our first industrial-scale plant mid-decade and for it to be fully operational a little later.

Business intelligence for the fibre, textiles and apparel industries: technologies, innovations, markets, investments, trade policy, sourcing, strategy...

Find out more